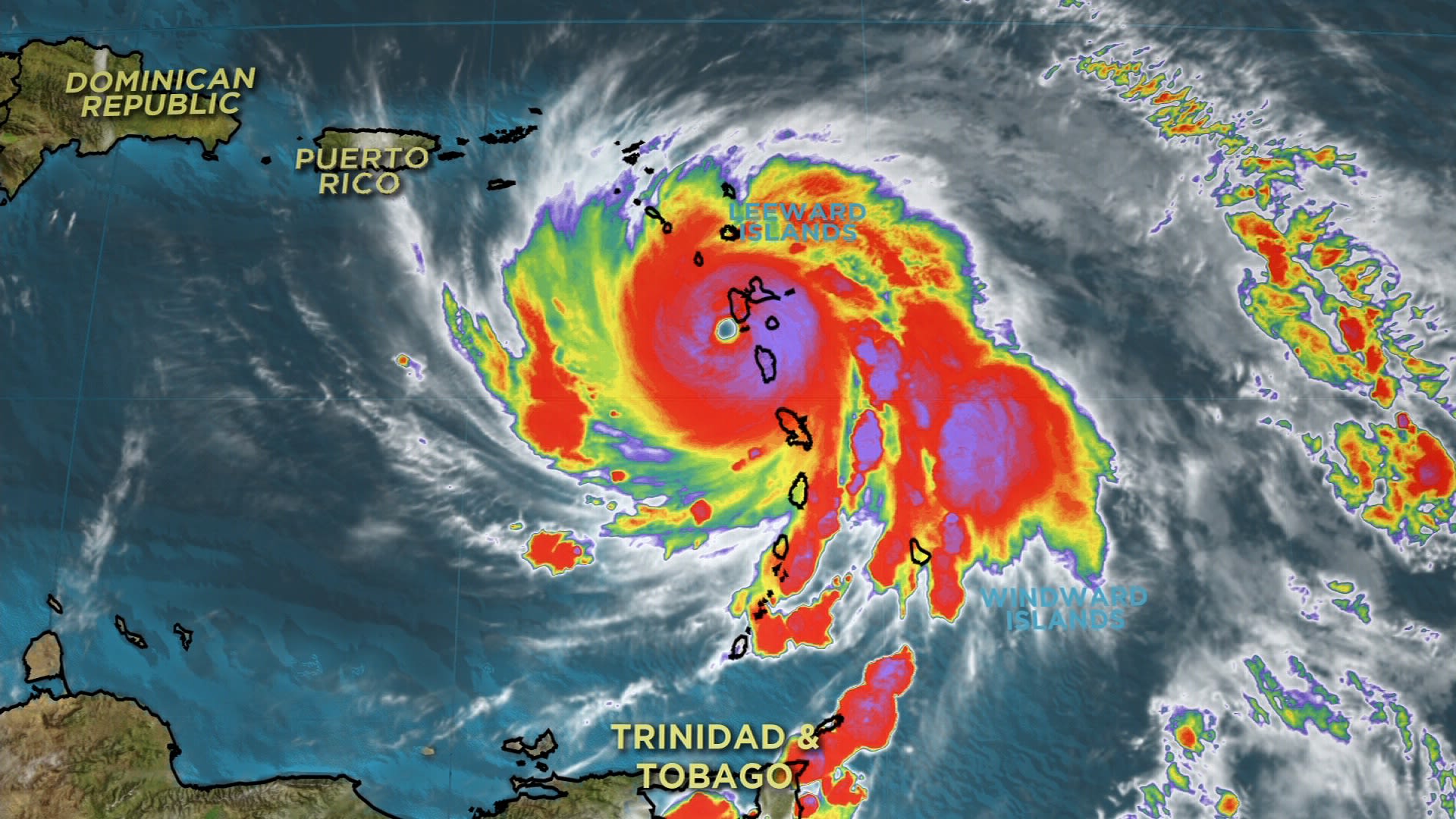

Before a Hurricane Maria, one of the biggest caused by climate change, Dianiz Roman and Wilfredo Gonzalez had never even considered leaving Aguadilla, the couple’s homeland in western Puerto Rico. But then everything changed in September 2017.

The disaster after the hurricane

A storm that killed almost 3,000 people and completely disrupted life on the island also destroyed both their workplaces- a funeral home and a petrol station.

Gonzalez remembers the months after the hurricane: “We were struggling; trying to get supplies, water, and food.” They claim that there was nothing else for them to do but travel thousands of miles north to Buffalo, New York, where Gonzalez’s sister had relocated a while back, to try their luck.

Gonzalez and Roman weren’t by themselves. Several thousand people have left the Caribbean island in the wake of Hurricane Maria for western New York state, which already has a sizable Puerto Rican community.

While it’s common for immigrants to settle in areas that can accommodate their cultural and linguistic requirements, Buffalo’s migration of climate migrants wasn’t entirely the result of that already-established community. The mayor of Buffalo named the city a “climate refuge city” months before Hurricane Maria made landfall, stating that Buffalo has “a tremendous opportunity as our climate changes.”

Since then, the city has released a relocation guide advertising the benefits

of relocating to Buffalo, including the fact that the city’s typical July temperature is a pleasant 71 F. The city updated its zoning regulations in 2017 to promote development in existing city corridors and started modernising its outdated sewage infrastructure in anticipation of a potential population increase.

Buffalo is not the only city which did that. A future with thousands more residents could—and should—look like, according to planners in towns like

Cleveland, Ohio; Ann Arbour, Michigan; Duluth, Minnesota; and others.

How can a city be protected from climate change?

The topic of “climate havens,” or areas in the northern parts of the United States near freshwater bodies of water where extreme weather events are uncommon, has gained popularity in recent years as deadly wildfires, record heat, and destructive hurricanes have a greater impact on day-to-day life there.

According to the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre, 675,000 Americans were uprooted from their homes by catastrophes last year, second only to Colombia among the 35 countries in the Americas.

Buffalo and Duluth have even been dubbed “climate proof” municipalities by one professor.

Many of these areas formerly relied heavily on manufacturing, making them potentially well-suited to accommodate a wave of climate migrants: Homes and city spaces were left behind when factories started to close in the 1970s and citizens went elsewhere in search of jobs. These places can now be reused.

Cleveland, which is located on Lake Erie’s southern shore, has about 30,000 unoccupied lots. There are more than 30 square miles of undeveloped land inside the boundaries of Detroit, which has lost nearly two-thirds of its population since its industrial heyday in the 1950s. The infrastructure in Duluth is currently adequate to support tens of thousands additional people.

According to Terry Schwarz, director of the Cleveland Urban Design Initiative, “we need to model different land use and development scenarios for population growth at the neighbourhood, city-wide, county-wide, and regional scales.” However, we’re only getting started at this stage.

While having access to land may be advantageous in some cases, other communities are looking at ways to modernise their housing stock by making it more resistant to extremes of heat and cold.

“Thinking through ways of reinvigorating the urban core is going to be central to having a more climate-resilient region,” says Nicholas Rajkovich of the University at Buffalo’s School of Architecture and Planning.

/Learn more about how climate change is affecting mental health/

A real haven from the climate change?

While many Great Lakes cities boast a mild temperature and plenty of space, some people don’t necessarily think that this translates into short-term climatic haven status.

Aside from Puerto Rican storm survivors going to Buffalo, there isn’t much proof that American climate migrants are already heading north on a large scale. Over the previous ten years, the populations of Cleveland, Duluth, and Buffalo have virtually remained unchanged.

“We learned from our research that community resilience is just as important as infrastructure or natural resources in predicting how well a city can adapt to climate change or increased migration levels,” explains Monica Haynes, director of the University of Minnesota Duluth’s Bureau of Business and Economic Research.

Furthermore, these populations are vulnerable to climate change. “Due to Canadian wildfires, we’ve had many days this summer with very poor air quality.” “As a result, the notion that Duluth is ‘climate proof’ is incorrect,” Haynes adds. “Climate change will have a negative impact on our city, as it will on the rest of the world.”

Nonetheless, the seemingly never-ending cycle of climate-change-related disasters calls into question which portions of the world will be habitable in the coming decades.

Scientists believe that stronger, longer-lasting hurricanes and rising sea levels will transform life in Florida and elsewhere, perhaps displacing 13 million people by the end of the century. Tornadoes, according to some academics, are spreading east into more densely populated areas of the South, potentially due to changing climate patterns. Wildfires are becoming a way of life in the West, and the recent damage on the Hawaiian island of Maui exemplifies the unpredictability of climate change.

Another deadly hurricane, Hurricane Fiona, blasted across Puerto Rico last September, killing over two dozen people, knocking off power for millions, and destroying crops.

Dianiz Roman and Wilfredo Gonzalez, on the other hand, were approximately 2,000 miles north of the storm’s devastation.

They believe they have adapted nicely into their new life after enduring the initial shock of the Buffalo winter. Both work in the local school system and are members of Buffalo’s thriving Puerto Rican community.

“When you walk into a store, you hear individuals conversing in Spanish and saying ‘hello’ to you. “It’s nice,” Roman remarks.

“You don’t get the extreme heat here that you do in Puerto Rico,” Gonzalez explains.”It took some time, but I grew to enjoy the snow.”